Every book is a house with two doors,

One at the beginning, one at the end.

And a book is a journey between two doors.

Alberto Ríos – Book with Two Covers

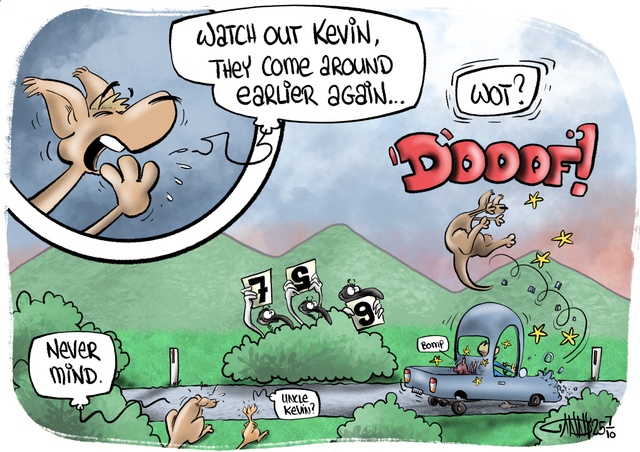

Whether you are sitting in a waiting room of a medical centre or commuting to work on a train, tram or bus, you can’t help noticing that just about everyone is engrossed in a phone.

The odd person who pulls out a book is now rare.

In Reading Mary Oliver celebrates the act of reading as a means of connecting with nature and the self.

She intertwines the experience of reading with the natural world, highlighting the meditative quality of both.

I read to find the world within,

to see the beauty in the ordinary,

to understand the rhythms of life,

and to connect with the earth beneath

It is however undeniable and understandable that books today are not regarded with the same respect as in the not too distant past.

Information can now be accessed in so many different ways via the internet.

A large proportion of Australians haven’t read or listened to a single book in the past year: almost 30 per cent according to recent research in The Guardian.

The saying A room without books is like a body without a soul.is attributed to Cicero (106–43 BCE).

But today bookshelves are increasingly seen on hard rubbish as minimalism takes over in homes, and books are deemed as clutter.

Even Op shops often display signs declining donations of books.

Some draw attention to the environmental impact of printed work yet like John Kinsella acknowledge their necessity:

The book in my hand

is both a forest felled

and the only way I know

to hear the forest speak

Libraries have reinvented themselves by offering services beyond books. Many may still associate libraries and bookshops with nostalgia as does Amy Lowell.

I go into the library,

Where the air smells of paper and varnish,

And the rows of books are lined like soldiers,

Silent, waiting to speak,

Waiting to tell their secret stories.”

Bookshops are struggling as numbers fall away.

Books in Australia have always been very pricey, far more expensive than in UK and USA.

Australia has had laws that restrict the importation of cheaper overseas editions if a local publisher has the rights and books attract 10 per cent GST.

This is meant to protect the Australian publishing industry, ensuring local publishers and authors get a fair go.

But it also means that a $15US paperback costs $32 in Australia.

Yiyi Osundare’s sees a bookshop as a place of discovery and learning, emphasizing the importance of literature in shaping society and individual thought.

In the bookshop, shelves are lined

with stories waiting to be told,

each book a doorway to a new world,

each page a step into the unknown.

Many studies show that people today struggle to sustain long reading sessions, that we are entering a new age of illiteracy, unable to read complex and long writing, preferring quick bite sized texts.

More and more are now challenged by the lengths of classics like Middlemarch, Anna Karenina, Crime and Punishment or a Dickens novel.

Or novels that are seen as literary which value art over formula, and use language and structure to deepen meaning, rather than relying solely on plot twists or commercial appeal.

Perhaps this accounts for the growing tendency of shorter contemporary novels.

Readers are more likely to read crime, romance, fantasy, memoir and dystopian fiction, showing people still turn to stories for escape and reflection.

So to jump to the conclusion that reading for pleasure is vanishing is premature.

It’s shifting form.

Fewer people may be curling up with long novels but stories still hold power in people’s lives.

The ABC has just been asking listeners for their nominations for the Top 100 Books of the 21st Century (so far): books published in English between 1 January 2000 and 31 August 2025.

All genres were eligible—fiction, non-fiction, poetry, etc

Final countdown will be on 18-19 October 2025.

But the fact remains that increasing numbers are swapping hardcovers for headphones and screens.

And more are turning to stories on their streaming services.

Some like Ellen Van Neeran, growing up queer and Aboriginal, in Throat writes of reading as both survival and reclamation.

I hid in books,

waiting for my story to appear.

Page after page,

a country I didn’t recognise.

Still I stayed,

and learned to name myself

between the lines

So does it matter how we read?

Some studies suggest people retain information better from print, especially when reading long or complex texts. Print encourages deep reading, whereas screens sometimes promote skimming or scanning.

Reading (for pleasure) is now low among most generations, and especially low among younger ones.

Younger readers who grew up with screens sometimes report little difference in comfort between digital and print.

And yet many struggle with reading set books in school.

Many adults still prefer print for leisure reading but will happily use screens for news, articles, and shorter forms.

Audiobook markets are booming.

Audiobooks are vital for people with visual impairments, dyslexia, or concentration difficulties.

These have made leisure reading more accessible during commutes, exercise, or chores.

They also democratize reading by letting people “read” while their hands and eyes are busy.

So does listening to audio books classify as reading? And if so what are the differences between the two experiences?

Books are more intimate and immersive, screens and audio books are more utilitarian and transient.

However, we tend to define reading too narrowly and exclude social media, online articles and audiobooks, which complicates comparisons.

Are you able to compile a list of your favourite books published in the last twenty five years?

Entries for the Woorilla Poetry Prize have now closed but put November 16 at the Emerald Hub in your diaries for the Gala Prize Presentation Event.