(PASSION FOR PROSE DINKUS)

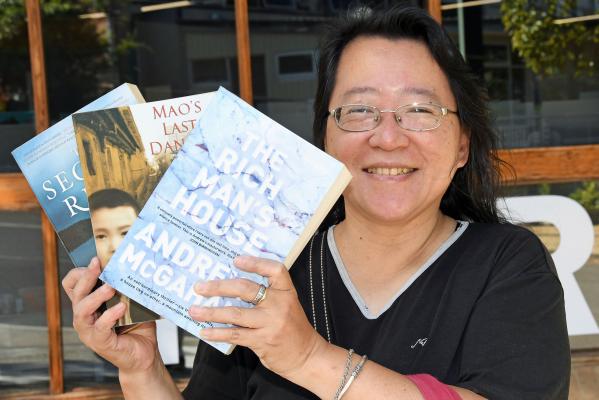

Warning: Here’s a 600-page book that’s absolutely unputdownable. Be prepared to have ohso-worth-it sore arms as Andrew McGahan’s The Rich Man’s House keeps you on the edge of your seat throughout the day and late into the night.

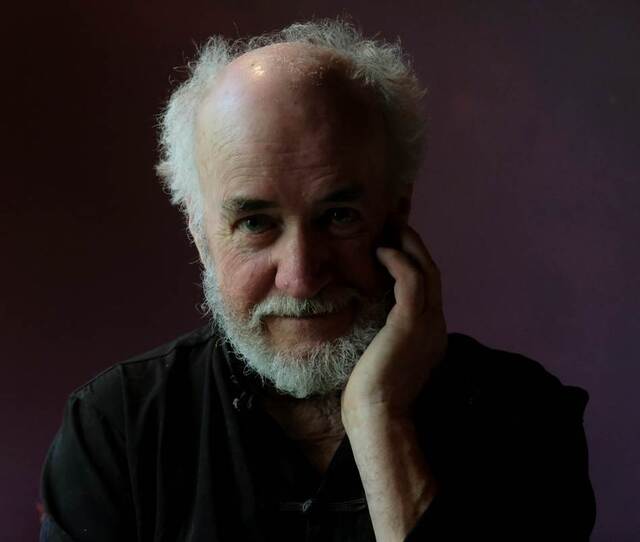

Winner of the 2019 Aurealis Award for Best Horror Novel, The Rich Man’s House was McGahan’s eleventh and final novel. The Miles Franklin Award-winning author spent the last weeks of his life finishing the book, before dying of pancreatic cancer.

The result is a haunting piece of speculative fiction featuring The Wheel, an unearthly mountain towering over the freezing Antarctic waters south of Tasmania. Since its discovery in 1642, the 25,000-metre geographical goliath of a mountain has defeated numerous climbers from across the world. It’s quite a thrill to read its masterfully constructed history.

Only one man has ever stood atop the mountain’s apex, known as the Hand of God. Decades later, Walter Richman, now a reclusive billionaire, painstakingly builds a mansion on the highest point of a neighbouring island. Whether the Observatory is Richman’s way to pay tribute to The Wheel as his greatest adversary, or to mock it as a subdued prey, is impossible to know.

But there’s something wrong with the Observatory, as Rita Gausse, daughter of the architect who designed it and subsequently died there, finds out upon her arrival. It is here, cut off from the outside world, that Gausse acutely feels – and fears – the ferocious, omnipresent and forever-patient forces of Mother Nature that she has long been sensitive to.

As the story unfolds, we see why Richman so insists that Rita is there to witness his final showdown against The Wheel. Reaching the story’s ending somehow feels like seeing a tsunami coming – something that is cataclysmic and catastrophic, completely predictable yet ultimately and overwhelmingly terrifying.

The Rich Man’s House is a microcosm of the history of man vs. nature. To this reviewer, it reads like an author’s fearless attempt to confront death. McGahan was careful to apologise in his Preface in case of any rushed or unfinished writing. Indeed, at least one critic has complained the novel “reads like an earlier draft of a more mature work”.

However, the raw and often brutal emotions detected throughout the pages are perhaps clues that help us comprehend the author’s anger, pain and frustration in the face of an untimely death.

While an artist’s ego may inspire them to triumph over death through art, a true artist would antagonise, amend and even alleviate the curious need of humans to dominate.

It is in between these two pursuits that conflicts arise and are explicitly conveyed in McGahan’s last writing. In the same way that The Wheel is so ingrained in the world of the novel that it feels real, we are reminded that no amount of scientific and technological advancement can replace or reconstruct a meaningful life.

A true page-turner, The Rich Man’s House calls for our respect, for ourselves, each other and the ancient, natural world.