For Gembrook local John Krzywokulski’s, his work has played a part in coping through grief.

“I lost a son to suicide in 2004, he was 29, I didn’t paint for a while,” Krzywokulski said.

“His grave was decorated by these friends who made totem type things out of tree branches, and they decorated them with feathers and messages and stones and coloured them rainbow colours.

“We just left the grave like that for a couple of years and it kept happening, his friends kept coming and putting these totems on the grave, and when I started painting again I thought I just didn’t really know what to do.

“I was [experiencing] total grief, so I used the elements on the grave as a cathartic experience and I started painting them and that got me back into the painting. The sticks, the feathers, the beach, he died overlooking a beautiful beach…[have] all became quite important elements in my own work.”

Krzywokulski’s parents were also displaced persons during the Second World War; his mum of Ukrainian descent and his dad Polish.

“During the war [mum] passed herself off as Russian because the Ukrainians during the war were basically getting wiped out by both sides; the Russians who came back then had an issue with them as they have right now with the Ukrainian war.

“She survived by being a Russian, but she was taken from school when she was about 16 in Ukraine because the German army came through and just took every able-bodied person; she never went back home and she never went back to her family, and she was put to work as a teenager.

“Dad was in the Polish army, which lasted for about two weeks. And then he went into the Polish underground resistance, which lasted for about six months before they were captured.”

An essay by arts journalist Dr Ashley Crawford, published in 2008, posits that Krzywokulski’s subsequent move to Australia – first to the bush are of Bonegilla migrant camp in Northern Victoria – has informed the colours present in his paintings; including sunsets.

Krzywokulski admits that sky and space do appear in his works.

“The conditions in Bonegilla were harsh…my family had it [very tough] and everyone had it very tough back then in Nissen army huts, but it was a new world and I think the expanse of space probably did have a subconscious effect on me in my paintings,” he said.

“The sense of space, sunsets, huge sky, clouds, beautiful cloud formations, and then the odd item in that incredible space which possibly subconsciously does affect a lot of the work that I’ve done where these spaces just counteracted by just a few items within the painting.”

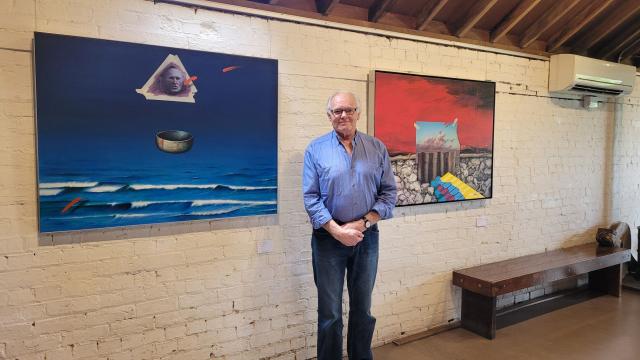

The disparate nature of his artworks is evident, with included symbols such as apples, bowls and branches as a nod to culture, religion and art history often inserted into open spaces of sky and water; often with only craftily painted sticky tape combining the two worlds together, Krzywokulski describes himself as a “maverick” in the art world.

“I’ve done the work and people realise that ‘hey, this is something we haven’t quite seen before; it’s fairly new.’ I’ve never been categorised as such, I haven’t been put into a particular category.

“Eventually, people realise that something different and new is going on here and perhaps requires a bit more attention than it’s had.”

Yering Station Art Gallery is currently presenting a three decade survey exhibition of Krzywokulski’s paintings called The Luminous Breath of Empty Space spanning from 1994 to 2024, which follows another survey exhibition held at the Cardinia Cultural Centre in 2022.

“Most of the responses have been positive; very positive from people that weren’t even interested in art before,” the surrealist artist said.

“I had a visitor’s book at the Cardinia show, and it was filled with quite amazing comments that really blew me away.

“I didn’t expect it from ordinary people coming off the street, but not only that, people who have followed me. There’s these people who came from overseas to see that show…they said it was one of the most powerful shows they’ve seen.”

Studying a Diploma of Art and Design at the Caulfield Institute of Technology, now Monash University, Krzywokulski formed a relationship with the renowned John and Sunday Reed; founders of the Heide Museum of Modern Art in Bulleen, after their adopted son Sweeney spotted his work in a student exhibition in the city.

“Even with the patronage of John and Sunday Reed, it wasn’t enough really to live off and the sales Sweeney made, they were okay, but certainly not enough to have any sort of decent living and expectations of owning houses and so on,” he said.

“I was lucky with that show that sold out because it gave me [money for] the land [in Gembrook]…I’ve done numerous jobs my whole life from when I left high school.

“I’ve worked in market gardens, I’ve worked on potato fields here… I’ve worked for motor mechanics in local mechanical shops.

“I’ve worked on fitting out houses and renovating houses with Dad when he was a carpenter and alive, so I’ve done a lot of things to bring in extra money… [art has] never been full time as such.”

In 1979, Sweeney Reed died by suicide at 34 years of age, followed by the deaths of John and Sunday in 1981.

“I was actually shattered at the time, absolutely shattered,” Krzywokulski said.

“I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t have an art dealer. I lost the patronage of John and Sunday Reed, so I actually took up teaching.

“Most of my career as a teacher was in Bialik College, which is a very prestigious, expensive private Jewish school in Hawthorn…. I did have a short period at Beaconhills College in Pakenham, I think it was about four years I was there, but then I went back to Bialik because they wanted me back as head of department.”

In the meantime, Krzywokulski remained exhibiting, and retired in 2009.

In 2016, his eutectic sculpture named “Tristan’s Journey,” a tribute to his late son, was heritage listed by Whitehorse City Council after it was originally awarded in 1974 as part of a national competition for a metal sculpture held by welded alloy supplier in Mitcham, Eutectic of Australia Pty Ltd.

Leading artists James Gleeson, Clifford Last and Frank Watters deemed Krzywokulski’s sculpture the winner, before it was placed in front of the company’s then headquarters at 666 Whitehorse Road.

“I think it’s incredibly important because general public probably don’t know but with the rapid development of the CDB with all the skyscrapers…we’ve actually lost a lot of very important sculptures that were in public places,” Krzywokulski said.

“People just don’t know where they went, whether they were scrapped, whether they were melted, if bronze was melted down or what, no one has any idea but they weren’t protected, they simply weren’t protected and we’ve lost them and that’s tragic, very tragic, so at least I know mine will be taken care of.

“I called it Tristan’s Journey after Tristan; that journey element is actually something that’s remained with me ever since.”

While he has got 50 years of work behind him, Krzywokulski said she us “not a coffee table book type artist” despite having a strong following “both nationally and internationally”.

“It’s adding something new to the contemporary art scene, so I think by word of mouth, and people doing a bit of research, they realise that ‘hey, this guy’s probably a bit of an outsider, but he’s important,’” he said.

“There’s nothing absolute that I’m trying to put out there; I’m not trying to be didactic or preaching to anybody as such, but I am hoping to make them think; think about life, think about reality, think about the illusions, think about what’s real and what’s important.”

The Luminous Breath of Empty Space will be on display until Sunday 3 March.

If the topics mentioned in this article have impacted you, help is available through Lifeline at 13 11 14 or 0477 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue at 1300 224 636 and through webchat or email support 24/7.