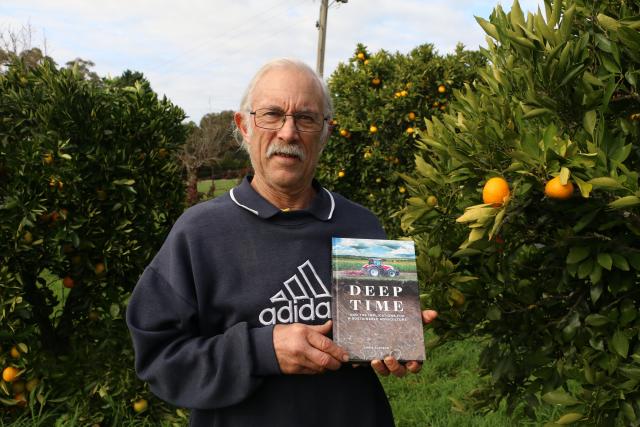

Macclesfield local Chris Alenson knows just about everything when it comes to soil, putting his mind to paper as he publishes his first book talking about sustainable agriculture.

Chris is an agriculture consultant, providing his service and knowledge to locals across Gippsland and the state for decades.

His speciality has been in providing ways in which farmers can get the best out of their soil in a sustainable fashion, whether it be for crops or pasture.

After 40 years in the field, 2023 is the year in which he finished and published his first book on the subject, titled ‘Deep Time – And the implications for a Sustainable Agriculture’.

With his book, Chris simply says, “What I’m asking for is more respect for the soil.”

This came to him four years from a place of both frustration and curiosity.

On the one hand, Chris, being in the agriculture field, had seen the environmental and agricultural reports become more and more grim.

“Every report that comes out from the IPCC or any agency around the world tells us that land degradation is increasing, biodiversity having extreme loss, particularly in Australia,” he said.

“We’ve got to do better.”

Precisely for Chris, the fact that sustainable practices are already so expensive in agriculture, yet still land degradation continues, is cause for action in his field.

One example he raises in his book is the famous Dust Bowl event in the USA during the 1930s where large stretches of land were hit with severe dust storms caused in large part by the destruction of topsoil in farming practices.

“We basically know the information and how to address things,” Chris said.

“The Dust Bowl was a disaster, yet the yearbook of agriculture back at that time, about the size of a telephone book, had all this massive information about how to fix things up.

“It’s led to my frustration, the information is there, how to do the right thing, but it hasn’t progressed.”

While on the other hand, the book was inspired by research in Chris’ original field in Earth sciences and geology, particularly of the concept of deep time.

“I was reading this geological book about deep time.

“What they were saying is that everything, most of our clothing, machinery on farms, etc, comes from geological processes that were millions of years ago and are not going to be repeated in our lifetime.

“So therefore government science should be thinking a little bit more about sustainable use of resources.”

Chris applies this concept to how he believes we should think about soil.

“So what’s the implications for agriculture if you follow that concept,” Chris said.

“Okay, it’s taken a few thousand years to form this typical Macclesfield soil, so we’ve got to have a bit of respect, if it’s taken that long to form it you don’t want to be turning it over with a plow and destroying it.”

Chris hopes to provide with his book a deeper understanding of the soil that can inform sustainable and enriching practices for farmer’s crops or pastures, rather than the more destructive practices prevalent across the world.

Chris came to understand soil from a background originally in Earth sciences, an academic teaching at Swinburne University and writing for others such as Charles Sturt University.

“There is a big overlap, I didn’t realise how important that was until you start dealing with the soil and start explaining to people where the nutrients for grasses come from, we’ll they came from something like this,” Chris says holding a piece of a rock exemplar of layer of rock found under the soil of his Macclesfield property.

“The dirt underneath us here is a bit of volcanic soil coming from a rock that is 40 million-years-old.”

“If you looked at this under a powerful microscope you’d see masses of different colours of the different minerals that are in there and each of those will have, for instance, calcium, potassium, things like that which actually feed the plant.”

This is only one section that forms the world always under our feet with millions of years of history, a story that Chris knows so much about.

“But 40 million years later you can end up with a soil that is quite devoid of those nutrients,” he said.

As is well known today, the anthropogenic influence of modern industrial society has intervened in this process with potential disastrous consequences.

Chris hopes to bring the questions and challenges in agriculture to the top of the agenda to promote the preservation of land for both the biosphere and farming.

When it comes to agriculture, Chris’ book wishes to dispel sustainability as a pipe dream, but rather as something that has been practised for the vast majority of human civilisation.

“This sort of farming, whether you call it organic farming or conservation farming, there was this emphasis on ensuring you put organic matter back into the soil,” he said.

“What they call multi-species pasture now, in the UK three or four hundred years ago they were having 15 different species for livestock to graze, that’s a concept that’s now being implemented across Gippsland.

“In terms of soil you can go back to the civilisations along the Nile, their fertility was renewed by the silt coming down the river system and then flooding and leaving it on the plains.

“Historically, looking after the land has been around for a long time, with industrial farming and mechanisation, we’ve got the ability to destroy soil a lot quicker than we have in the past.”

It’s this international scale to agriculture, which has given destruction of soil, depleted biodiversity and the overuse of such things as artificial fertilisers.

Chris addresses the future of agriculture in his book with the many global challenges, but with his work as a consultant his work also looks to benefit local farms and show them sustainability is a better alternative all round.

“There are key ecological principles that farmers really should follow, like in a natural system where everything is recycled as much as possible,” he said.

The book includes discussion and demonstrations that can minimise waste on farms, including recycling for a more integrated closed system on the land.

“The approach should be let’s get the best out of the soil we possibly can before we go adding an input, and if we do choose an input it’s going to be an appropriate one, not one that will damage the environment,” he said.

“It’s the whole idea of trying to get people to think more about sustainability, you’ve got to find that balance between economic viability obviously and producing food without degradation – in other words, produce within the constraints of your environment.”

Gippsland’s farms are predominantly for livestock where good pasture is key. Chris has provided for these farms and believes there is just as much to manage with the soil as crops.

“I do say in my book there are many grazing properties that are actually doing quite well here, but ultimately if there is a decline in organic matter and biodiversity is lacking then we have got to do better,” he said.

Chris works at his own yard, a ‘laboratory’ he calls it, to see what works for pasture, regularly digging samples to test the soil and provide advice to locals.

“If we were out on a pasture or livestock farm we will be having a look to see how the soil crumbles as an illustration of oxygen that gets in the soil, root extension – that’s how far the roots are going into the soil – because at the end of the season around about 50 per cent of these break down and form organic matter that feed next year’s grasses,” Chris said while examining a sample he just dug from his property.

“Species diversity, plantain here, that’s a really beneficial herb, high in protein and trace elements.

“It has to be rotated properly so there is plenty of opportunity for the grass to bounce back, in a sense these are the solar collectors.

“If it’s grazed too short, the reliance of this system is compromised, it may take another three to four weeks to bounce back to grow more pasture.”

Big or small questions, Chris has an answer and it comes from a long-term sense of responsibility which he hopes more will take on.

“We need to a bit better, I believe it was the native-American tribe around the Great Lakes in North America, they had what they called seven-generation sustainability, in other words they wouldn’t take on a management decision if they thought it would affect any of the seven generations into the future.

“I know there are a lot of producers on the land that follow, in a sense, that way and they’ll say okay I’m looking at this land here if I go and plow that up or do that, I know I’m going to do damage that my children won’t be able to repair.”