With the topic of The Voice referendum scattered about on news platforms and in conversation across the country, it can be hard to find out what The Voice is really about.

The referendum is about a vote on the proposed alteration to the Australian Constitution, split into four subsections:

The first (subsection 129 I), outlines the recognition of First Nations peoples as the traditional inhabitants of Australia. As documented in the advisory report for the voice referendum, this form of recognition will consist of “introductory words to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia.”

The second part (subsection 129 II) introduces the establishment of a new constitutional power called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. The third and fourth outline the “representation-making” function of The Voice and navigate the parliament’s ability to make laws in accordance with and in relation to The Voice entity respectively.

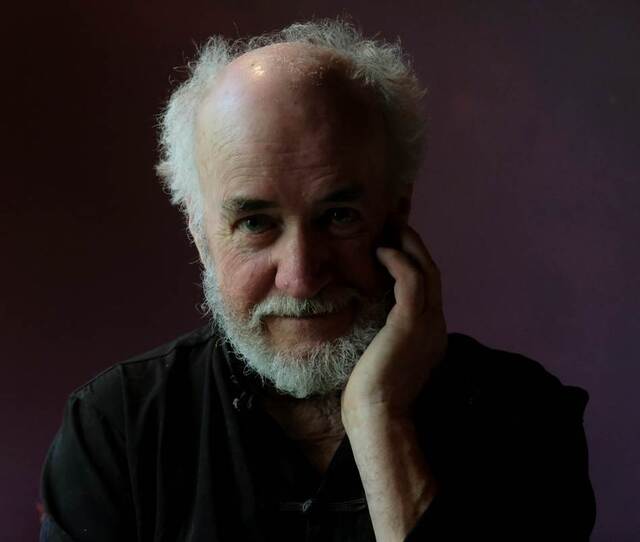

Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Melbourne Cheryl Saunders said if the referendum is successful, the Governor General needs to give his ascent for the change but that will be a formality.

“The government has no power. If the people vote yes, the constitution is changed. If the people vote no, the constitution is not changed,” she said.

Purpose

The question on the ballot will read as ‘a proposed law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?’

Prof Saunders said what The Voice will look like will be a matter for legislation.

“The proposal provides the parameters for Parliament when setting up The Voice which can then amend that legislation over time. The legislation won’t be set in concrete, no legislation is,” she said.

“The power of The Voice will be there for the parliament to use and while legally the government is not forced to use that power, politically it has to enforce it and will.”

Action

After voting, if the result of the referendum supports constitutional change, there may be opportunities to provide public submissions to parliament. These submissions would be written in the same manner in which you would write a regular parliamentary submission.

“As persuasively as you can,” said Prof Saunders.

“I suspect the referendum consultative council (check) might be the core of it, however, there is likely to be a consultation beyond that. I also think it’s very likely that the parliamentary committee in charge will call for public submissions.”

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has recently announced plans to set up a broad-based parliamentary committee to deal with the drafting of the legislation.

“I’d expect that there would be public hearings as well. If the parliamentary committee has any sense it will move around the country to make that easier for people,” Prof Saunders said.

“I imagine that there will be consultation with Indigenous people themselves and that there will also be a lot of consultation in the parliament.”

It has been established that The Voice will consist of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members from each of the states and territories including some from remote communities.

“There are questions about signs and representation, however, there are published principles indicating that there is to be a gender balance, old and young, regional representation, urban regional and rural remote representation,” Prof Saunders said.

“If the change is approved, the most obvious thing for people to be aware of is the drafting of the legislation and what goes into it, if they are interested enough to be involved in that as well. Once the legislation is through, an important thing for people to be aware of is how well it’s working.”

How The Voice Referendum Came About

Prof Saunders said people who study Indigenous history say that they can go back decades and even centuries to the 19th century when Indigenous representatives called for a representative body.

“The process for asking Indigenous Australians what meaningful representation would look like, was to establish deliberative groupings around the country called the dialogues. Each of these 13 dialogues in different parts of the country,” she said.

“But everybody discussed what they would hope to get out of recognition and therefore, what meaningful recognition would look like.”

The 13 Regional Dialogues were represented by over 250 Indigenous Australians at the 2017 First Nations National Constitutional Convention near Uluru. The Uluru Statement From the Heart was released on 26 May 2017, containing the call for The Voice.

Post-referendum consultation

Prof Saunders said the government, particularly at the central level, is not particularly consultative.

“Except with peak bodies sometimes so opening up the Commonwealth to more consultative processes would be broadly advantageous all round,” she said.

“If the referendum were not to be approved, it would still be appropriate for the Indigenous people themselves to be consulted on what, if anything, comes next at the national level. The idea came from them in the first place through the convention so it might be appropriate for it to go back there.”